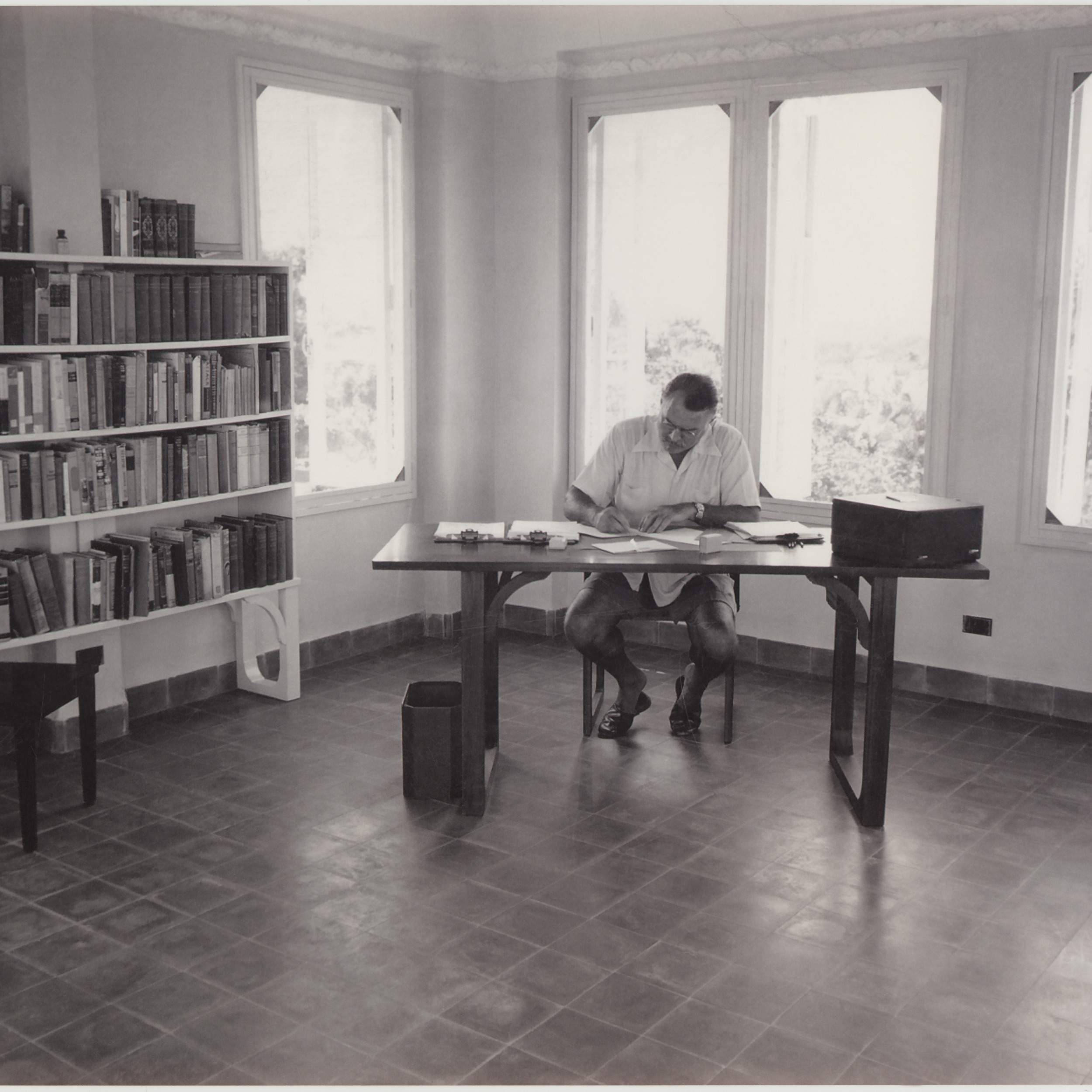

A new documentary series follows the life of one of the world’s greatest writers -- who was also born and raised in Oak Park -- Ernest Hemingway.

The Chicago-suburban native was one of the 20th century's greatest writers, and the man behind classics like A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls.

“This is a grand, complicated, dark, romantic tale,” director Ken Burns said of the author, whose life and style has reached legendary proportions almost 60 years after his death. “But at the heart of it is somebody struggling to figure out a new way to express the stuff of the 20th century in basic, elemental language.”

Reset sat down with renown documentary filmmakers Burns and Lynn Novick to talk about their new three-part, six-hour documentary, Hemingway, airing on PBS on three consecutive nights this week. The pair crafted the story from the prolific letters and documents the writer left behind, which Novick said revealed his “inner life … what he was thinking at pretty much any given moment.”

Here are edited highlights from the conversation.

On “a more vulnerable” Hemingway

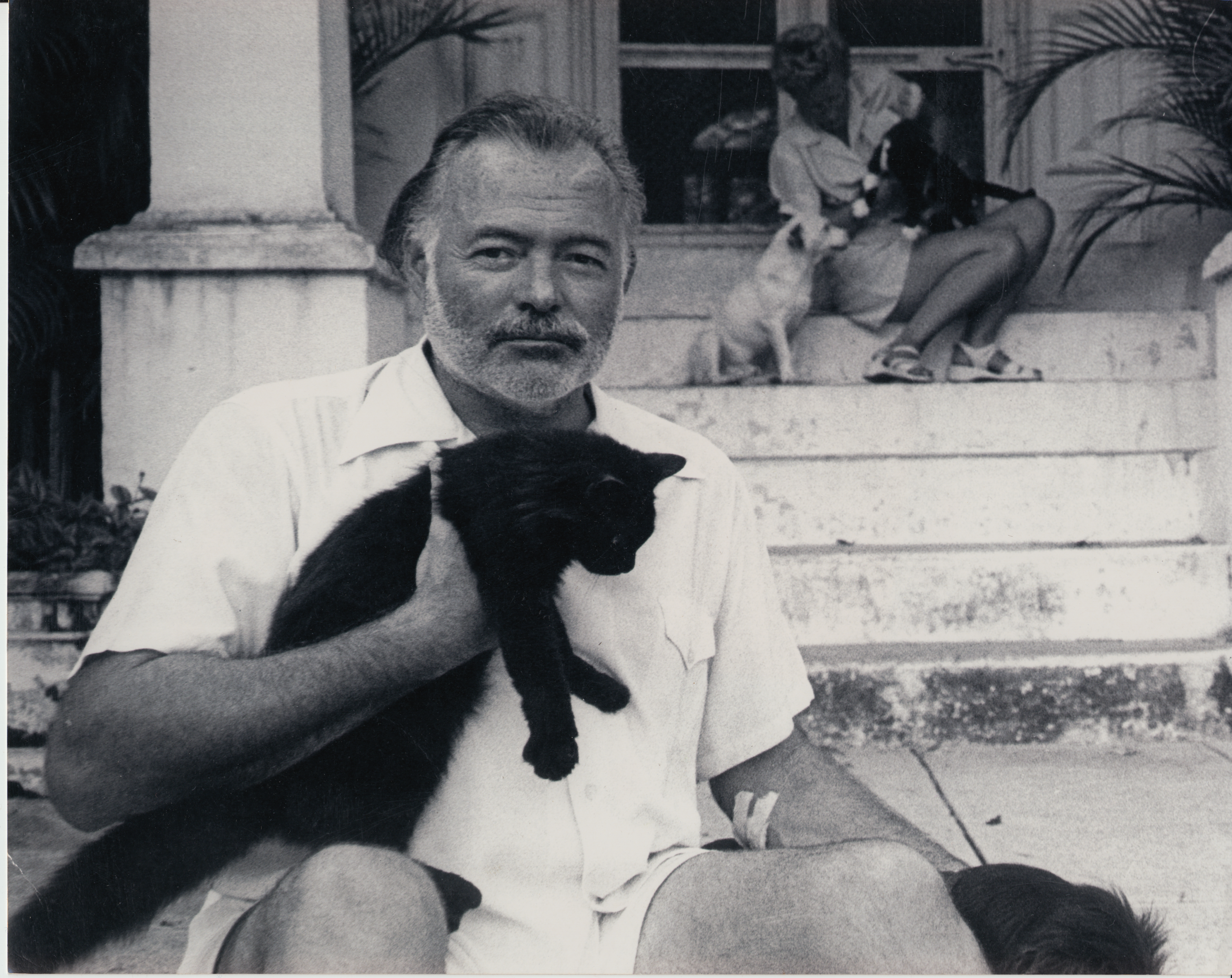

Burns: This is the story of one of the 20th century's greatest writers, and a person who had a profound effect on not just American literature but all of world literature -- and who nonetheless has the most complicated kind of personal life. He created a mythology that is so impenetrable, it took us, Lynn and I, six and a half years just to pierce the veils of that kind of overhyped masculinity to get at a more vulnerable, a more empathetic and more interesting Ernest Hemingway.

On his family and upbringing in Oak Park

Burns: At first glance, he's got this comfortable, middle class life in Oak Park, a well-to-do suburb of Chicago. And yet there is a family history of mental illness. Indeed, in this nuclear family, four of the eight members of his close family -- two parents and six children -- will die from their own hand. And his mother is sort of high-strung and dramatic, and is self dramatizing, all features that Hemingway will have.

His father's suicide causes him to reconsider everything. Hemingway sees him as a coward and yet blames the mother. That is a very complicated dynamic. In the midst of the outwardly prosperous, suburban life is a very tragic and complicated family. And it's all going to add to the PTSD of WWI, concussions and alcoholism and other things [that are] going to inevitably not turn out well for Ernest Miller Hemingway.

On his near death experience in World War I

Novick: It's probably fair to say that he was a different person after the war, and he might have said that himself. After an explosion in which he was badly wounded with multiple shrapnel wounds -- his leg was torn to pieces, and he had a big head wound -- he said he felt his soul leaving his body. It was like a handkerchief being pulled out of a pocket and floating around and then coming back. And that was a searing, traumatic experience and probably a profoundly spiritual existential experience as well that never left him. So he had a sense early on of the fragility of life, the fact that it can all be taken away, the fact that you can't control your own destiny. These are existential human themes.

On Hemingway’s love of love and how heartbreak shaped his life

Burns: Hemingway was a serial monogamist. He loved falling in love. But receiving of a Dear John letter from his first love, I think, really, totally uppended him in a similar existential way as the experience in WWI at 18 years old.

I think he enjoyed the romance of it. He's very loving, and he understands the intimacy between a man and a woman.

But a lot of what we characterize as his misogyny in stories and in real life is legitimate and inexcusable and unforgivable.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. Press “Listen” to hear the full conversation.