The Chicago Park District is about green space and recreation. But for the past two decades, its main offices were on several floors of a Streeterville high-rise, blocks from any parks.

That’s one reason the district’s move to 48th Street and Western Avenue in May was momentous.

“It brings the park district staff in closer contact with the people we serve,” Rosa Escareño, the district’s CEO and general superintendent, said as WBEZ’s Reset walked through the new building.

The building contains both a park fieldhouse that’s fitted out with a basketball gym, fitness equipment and such, and the offices for Escareño and about 200 staff. And the two uses mingle with glass walls, second-story overlooks and courtyards.

The move also brought a bold, handsome new piece of architecture and a 17-acre greenspace to Brighton Park, previously one of the city’s most park-deficient neighborhoods, according to Heather Gleason, the district’s director of planning, who quarterbacked getting the place built. The site, made up of several former industrial parcels, had 14 disused underground tanks that had to be removed, a large piece of environmental remediation.

John Ronan, the building’s architect, picked up on this theme of renewal when designing the park district’s headquarters building for the east end of the site. Two of the primary materials he used are reclaimed Chicago common brick from a pair of buildings that were demolished and ash for wood finishes on the main staircase, the gym floor and bleachers.

“This whole project is about renewal,” Ronan said. The concept also shows up in the landscaping with native plantings on the north and east sides of the building.

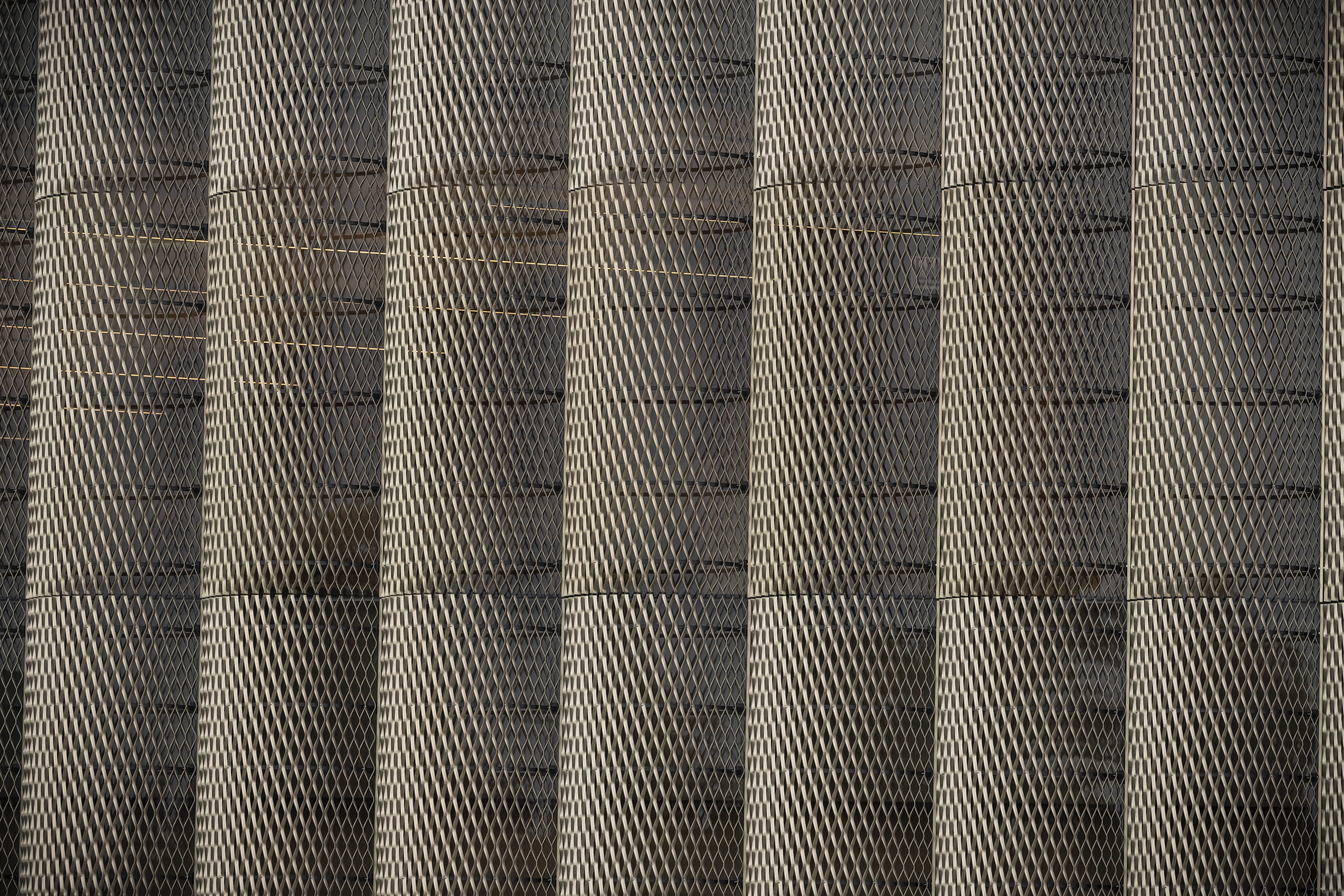

Those are details visitors will see when they get inside the building. What they’ll see first is the building is circular, 240 feet in diameter, according to Ronan, with brick and glass surrounding the first floor and a wire mesh surrounding the second. The mesh curves out from the building in waves, making it appear to be rippling or billowing. The building is the latest dramatic design by Ronan, who also did the Poetry Foundation’s River North headquarters, the Kaplan Center at IIT and the Gary Comer Youth Center in Grand Crossing, among many others.

At the park district building, the wire mesh serves two purposes, Ronan said. The mesh is a sunscreen for the glass walls behind it and prevents birds from flying into the glass. Lower-level glass doesn’t have the screen, but most of it is in enclosed courtyards, where it poses far less threat of either heat loss or bird kill. Where there’s any risk, the glass there is fritted with white dots that help birds see there’s an obstacle they can’t fly past.

There are two more noteworthy elements on the exterior.

First, this is a walk-through building with wide passageways that lead to interior courtyards. These make it possible to get daylight into the inner parts of a building that’s 240 feet wide and, Escareño said, enhance the interactivity between park employees and users by increasing the places where one might see the other, for example, sitting at the courtyard tables to have lunch.

Second, the bricks project out from the wall at seemingly random spots. They help the building’s acoustics: With parallel brick walls, sound could bounce around, Ronan said, but those projecting bricks break it up, helping to quiet the space. The placement, he said, was intentional. The bricks are close together on the upper reaches of the walls, but down at ground level they’re much farther apart to discourage wall-climbing.

“For rock climbers, we have climbing walls in other parks,” Escareño said.

Inside the office portion is a lobby two stories high that leads to a stunning space: the staircase, wrapped floor and walls with ash and capped by a long linear light that fills the ceiling. The lobby had to be grand, Ronan said, as befits the size and history of the Chicago Park District.

That might suggest the rest of the interior is opulent or grandiose, but once you get past the staircase, there’s little that’s ostentatious about the offices and conference rooms. They have a nice mix of brick and glass, with the wire mesh outside the windows letting the sun cast intriguing shadow patterns on the floor, Gleason said. There’s a complement to the pattern in the mesh: On the walls, the bricks break out into a checkerboard pattern in several places, alternating brick and void. It’s another way to soften the acoustics of brick walls, Ronan said.

There are also glass-walled spaces, including an employee break room that has one glass wall overlooking an exterior courtyard and another paralleling that one and overlooking the gym.

The gym down below has brick walls, checkerboard panels, multiple shades of ash lining the floor and wrapping from there up into a picturesque set of bleachers, and daylight coming in from upper-story windows and skylights.

In the 2010s, Mayor Rahm Emanuel pushed to get city institutions out into the neighborhoods, particularly those that were under-resourced. That effort resulted in the City Colleges staff mostly scattering from a Loop headquarters to spaces at the various colleges, and the city’s Fleet Management department moving from a North Side site to Englewood, bringing 200 jobs with it.

The latest department to move is the park district, a move that cost about $69 million, according to Gleason, for development of the whole 17-acre site, including park, athletic fields and the hybrid headquarters/fieldhouse building.

Dennis Rodkin is the residential real estate reporter for Crain’s Chicago Business and Reset’s “What’s That Building?” contributor. Follow him @Dennis_Rodkin.

K’Von Jackson is the freelance photojournalist for Reset’s “What’s That Building?” Follow him @true_chicago.